09 Aug Colourful Conversation

This piece by Oluwalogbon Akinnola was shortlisted in the Colour Group (GB) Prize for Outstanding Communication on Colour 2021.

Introduction

I like to think I was a normal child. My siblings would argue otherwise but they are not writing this, so my statement stands. I liked videogames, was no great fan of homework, and I loved TV. It was a love I inherited from and shared with my dad. I could sit there for hours watching anything with him or by myself: James Bond, Bewitched, Pokémon, anything. My doting, unofficial godparents were The Simpsons and Disney. In fact, there was only one thing I did not watch: black and white shows. Monochromatic media? Gross. Does not matter how important they are to cinema, I refused to watch Citizen Kane or Seven Samurai. To me, colour played a vital role in transporting me into the scene on the screen. I needed to see the blue of the sky and the yellow of the sand to feel like a part of the world. Colour made what I was watching feel alive. Now, a good 20+ years later, I think I know why: colour is communication.

What is colour?

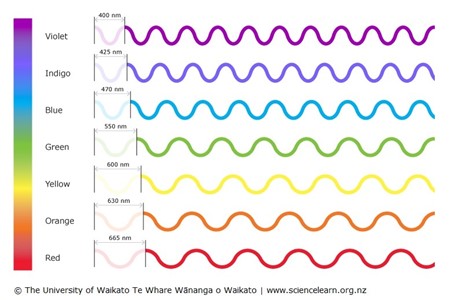

I have outgrown my disdain for black and white movies but my interest in colour has not waned. Before explaining what I mean by “colour is communication”, I think it’s important to understand what colour is. The OED says that colour is “appearance that things have that results from the way in which they reflect light”. Light is an electromagnetic radiation that our eyes can process. It travels as a wave and its wavelength, the distance between the peaks of the wave, determines the colour our brains perceive. When the light shines on an object, the object only reflects certain wavelengths and so it looks like a certain colour! A black object does not reflect, and a white object reflects everything. It is also why a red t-shirt looks black in blue light, there is not any red to reflect. So, colour is one of the constituent parts of the visual language that we use to interpret the world around us. Given that 50% of all neural tissue is connected to vision and 2/3 of all brain activity is related to vision while our eyes are open, we depend on colour. No wonder I never finished It’s A Wonderful Life.

Visual Signals

All that visual information is not just for show, however. Beyond telling your Lennys from your Carls, animals and plants employ colour as ““. . .signals, colourful communications from one organism to the other” (Murphy and Doherty, 2005). For example, bright colours are often warnings to would-be predators. The red colouring of ladybirds is effectively a “Don’t Eat Me” t-shirt. It indicates to birds that they taste bad; the brighter the red, the worse the taste. Similarly, the Fly Agaric fungus is a bright red mushroom with white spots. They may look Mario’s Super Mushrooms but eating one would cause you to hallucinate, sweat excessively, and vomit not double in size. Eat at your peril. It is not just red that warns of danger, though. The Greater Blue-ringed Octopus is highly venomous and the distinct colouring on a skunk tells you to stay back, or else.

Not all colour is to ward others away, however. Sometimes it is the exact opposite. Flower petals are brightly coloured to attract pollinators to the flower so it can reproduce. In animals, the male of some species is very colourful for the same purpose of attraction. It helps them stand out of the crowd and attract a mate for the season. Take the peacock for example: a peahen is instinctively more attracted to the males with larger, more colourful tails. And who can forget the Australian Squid featured in David Attenborough’s Blue Planet? The male cephalopods attract females through a balletic display during which they change colour!

Shier animals use colour to not be heard. Many have colours that let them blend into their environment. Some resemble their surroundings: polar bear fur looks white, parakeets are a leafy-green, etc. Other animals use disruptive coloration – a non-repeating pattern of strongly contrasted colours. This breaks up the outline of the animal, making it difficult to make out features. Think of a leopard and its spots: it makes it hard to spot in the undergrowth as it gets ready to pounce.

Express yourself

Humans also use colour to communicate. Think of traffic lights, sports teams, which bins to put out on bin day – there are myriad ways we use colour to send a message. Colours let us identify things or be aware of danger. It conveys information in fractions of a second that can be the difference between life or death. Beyond the practical, however, humans use hue to express themselves. We wear black to funerals to show our grief, we fly a rainbow flag to support the Queer community, we use colour in art to transform the world around us into magical landscapes we can meander through. Context is key, however. A white dress may be fitting for a wedding in the West, but white is more commonly associated with funerals in countries like India or China.

Beyond communication, colour can affect us physiologically and psychologically. For example, red has been found to be inviting and stimulating, speeding up blood flow. More blood to the digestive system makes you hungry, which is why so many restaurants use red in their signs and décor. Similarly, the city of Nara, Japan installed blue lights on railway platforms to reduce suicides by 84%. A simple change of colour saved lives.

Join the conversation

Colour plays many roles in our lives, but communication is an integral one. There is a never-ending dialogue happening all around us. What are the hues telling you? What are you telling the world? I encourage you to read about colour and visit galleries, listen to shows like the Owning Colour series that ran on Radio 4, and join bodies like the Colour Group to learn more about the language. Be part of the conversation.

References

Murphy, P. and Doherty, P. 1996. The Color of Nature., Pg 20, Chronicle Books, San Francisco, Ca.

Oluwalogbon Akinnola developed an interest in colour after learning about complementary colours in secondary school art class. While his artistic endeavours did not progress much further, his passion for science and science communication did. He enjoys exploring how art and science intermingle and pulling out the narratives the two produce when considered in concert. Though now working as a bioengineer, science writing remains an enjoyable hobby for Oluwalogbon and he maintains a blog that includes his work as well as other musings.

Oluwalogbon Akinnola developed an interest in colour after learning about complementary colours in secondary school art class. While his artistic endeavours did not progress much further, his passion for science and science communication did. He enjoys exploring how art and science intermingle and pulling out the narratives the two produce when considered in concert. Though now working as a bioengineer, science writing remains an enjoyable hobby for Oluwalogbon and he maintains a blog that includes his work as well as other musings.